Method

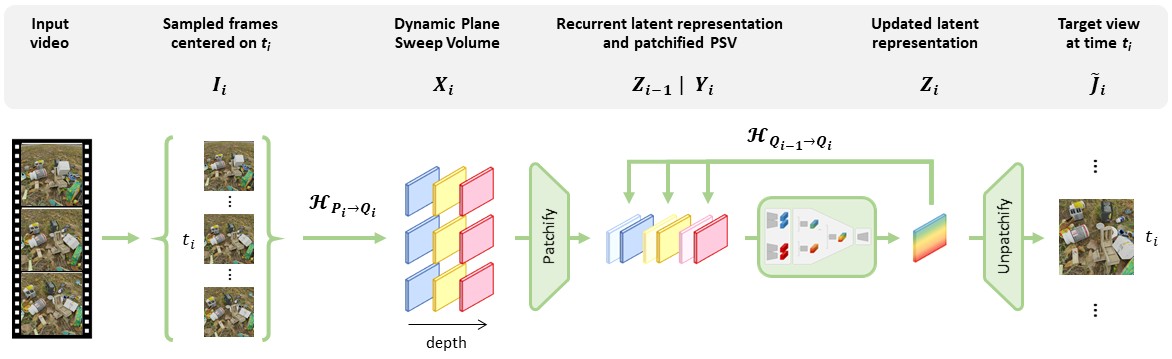

Overview of GRVS. For a target view $\mathbf{J}_{i}$ at time $t_i$ and with camera parameters $\mathbf{Q}_{i}\,$, our Generalizable Recurrent View Synthesizer consists of 5 stages. 1) The selection of $V$ input views $\mathbf{I}_{i}$ uniformly sampled around the time $t_i\,$, with corresponding camera parameters $\mathbf{P}_{i}$. 2) The projection of $\mathbf{I}_{i}$ into a dynamic plane sweep volume $\mathbf{X}_{i}$ using the homographies $\mathcal{H}_{\mathbf{P}_{i} \to \mathbf{Q}_{i}}$. 3) The patchification and reshaping of $\mathbf{X}_{i}$ into a downsampled tensor $\mathbf{Y}_{i}$. 4) The latent rendering of $\mathbf{Y}_{i}$ into a hidden state $\mathbf{Z}_{i}$ using the recurrent hidden state $\mathbf{Z}_{i-1}$ projected using the homographies $\mathcal{H}_{\mathbf{Q}_{i-1} \to \mathbf{Q}_{i}}$. 5) The decoding of $\mathbf{Z}_{i}$ into the predicted output $\mathbf{\tilde{J}}_{i}$.